My first experience with fossil shark teeth came at a Cretaceous site in New Jersey known as Big Brook. Having come off the stream, I was excited by the material I found. A mosasaur tooth was the best item, but I thought the Brachyrhizodus (ray) teeth the neatest. Shark teeth were numerous, but I really had no idea what they were. An older gentleman approached and offered to identify my finds. There seemed to be an abundance of larger teeth he referred to as 'goblin' shark. Before departing, he suggested I pick up a copy of a pamphlet he wrote some 15-years earlier - Fossil Sharks: a pictorial review. In one day I encountered two icons of New Jersey's Cretaceous, Scapanorhynchus1 and Gerry Case.

It was long before the Internet era and getting information on this 'goblin' was no easy task. I came to learn that this was not a common genus and the few available specimens were securely housed in museum collections. For me, I came to know the dentition more from the fossil species attributed to MITSUKURINIDAE than the few published papers on the extant species - this would continue for over a decade.

It was long before the Internet era and getting information on this 'goblin' was no easy task. I came to learn that this was not a common genus and the few available specimens were securely housed in museum collections. For me, I came to know the dentition more from the fossil species attributed to MITSUKURINIDAE than the few published papers on the extant species - this would continue for over a decade.

The availability of Mitsukurina material changed abruptly in April 2003 (Hubbell pers. com.). Fishing off the northwest coast of Taiwan in 2000 feet of water, commercial fishermen started boating hundreds of goblins in the three to four meter range. These local fishermen were quite secretive with the details, but indicated that they were mostly males. With luck and perseverance, Gordon was able to obtain a number of dentitions.

The Goblin Shark

According to Compagno (2001) the extant species is a large (to 3.8m) poorly known bottom-dweller of outer continental shelves, slopes and sea mounds (to over 1300 meters) which has been reported from scattered locations of the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its appearance is rather bizarre — pinkish-white in color, soft & flabby body, long caudal fin, elongated paddlefish-like snout and highly protrusible jaws. The snout is thought to be employed for prey-detection, and the long slender teeth are optimized for fishes, shrimp and squid. (Unlike the above caricaturization, the jaws would only extend during prey capture.)

The Goblin Dentition

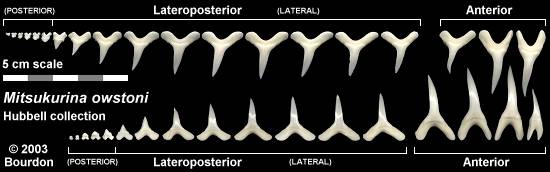

The goblin has a tearing2 dentition made-up of long slender anterior and lateral teeth (posterior files are of a crushing design). The lingual crown face is strongly striated and the cutting-edge is smooth and complete. Teeth may bear reduced lateral cusplets, usually more common/developed posteriorly. Although there is a clear diastema3 between anterior and lateroposterior teeth, there is no strong 'intermediate bar' differentiating the upper anterior and lateroposterior hollows4 as might be seen in Carcharias. The upper and lower jaws (palatoquadrate & Meckel's cartilage) appear thinner than those of the modern sand tigers.

The goblin has a tearing2 dentition made-up of long slender anterior and lateral teeth (posterior files are of a crushing design). The lingual crown face is strongly striated and the cutting-edge is smooth and complete. Teeth may bear reduced lateral cusplets, usually more common/developed posteriorly. Although there is a clear diastema3 between anterior and lateroposterior teeth, there is no strong 'intermediate bar' differentiating the upper anterior and lateroposterior hollows4 as might be seen in Carcharias. The upper and lower jaws (palatoquadrate & Meckel's cartilage) appear thinner than those of the modern sand tigers.

Three teeth emanate from the upper anterior hollow (A1-3) and four from the lower (A1-4)5. Upper lateroposterior files include 10-11 elongated 'lateral' cutting teeth and eight to twelve low-crowned 'posterior'6 teeth. The fourth lateral is the largest lateral. In the lower jaw, seven to eight teeth are of the lateral-design and about a dozen would be deemed 'posteriors'. The first 'lateral' is the largest in the lower lateroposterior hollow. Upper intermediate teeth may or may not be present (Hubbell pers. com.).

Footnotes

1. Scapanorhynchus texanus (ROEMER 1849), a Cretaceous goblin shark. For additional details see the "Genera" section of this website. David Ward (pers. com. 2003) points out that texanus is most likely not a Scapanorhynchus due to its presence in shallow water/high energy sediments, a very un-Scapanorhynchus/Mitsukurina environment.

2. A tearing dentition is characterized by elongated teeth with a strong cutting edge. Anterior positions have multiple functional rows. Laterals are usually broader (approaching the cutting-design) with one row functional.

3. A better image of the diastema can be seen in the website's Extant Dentitions slideshow.

4. Siverson (1999) coined the terms anterior hollow, intermediate bar and lateroposterior hollow to more specifically ascribe lamnoid teeth to various positions of the dental groove. Although the term dental bulla had been previously employed for Siverson's anterior hollow, the other tooth-producing regions lacked a specific name. The specificity of Siverson's terminology appeals to me and has been incorporated here and elsewhere on this website.

5. Certain authors [i.e., Applegate (1965) and Shimada (2002)] refer to reduced teeth from the mesial position of the anterior hollow as symphyseals/parasymphyseals. Some authors [i.e., Applegate & Espinosa-Arrubarrena (1996) and Shimada (2002)] prefer to use the term 'Intermediate' for teeth emanating from a distal position of the anterior hollow. It is this author's opinion [and that of Siverson (1999), Cunningham (2000) and others] that the teeth produced by the anterior hollow should be referred to as anteriors — symphyseals are not present and only the 'bar' or diastema between the hollows produce intermediate teeth. The two recommended references for this disagreement would be Siverson 1999 and Shimada 2002. Steve Cunningham discussed this matter in detail in the Carcharias Dentition slideshow.

6. Some participants of this project (i.e., Shimada and Siverson) preferred not to use the term 'posterior' for the reduced teeth of the lateroposterior hollow, arguing that the teeth morph in such a gradual fashion that there is no odontological feature(s) that can differentiate this transition (from lateral to posterior). The lack of a definitive break-point is certainly true, but in many cases (particularly in species such as Mitsukurina & Carcharias) there are stereo-typical lateral and posterior tooth-designs. It this author's opinion (and others, i.e., Heim and Cunningham), that the lack of quantitative resolution is overshadowed by the subjective clarity provided by the grouping of teeth into lateral (cutting) and posterior (crushing) buckets.

Acknowledgements

As with most elasmo.com presentations, this has been a collaborative effort in gathering, assembling & presenting the data/images and the subsequent reviewing of the final content — some of which was quite exuberant and thought provoking. I'd like to thank the following individuals for their participation: Steve Cunningham, Bill Heim, Gordon Hubbell, Don Moore, Bob Purdy, Kenshu Shamada, Mikael Siverson and David Ward.

Cited References

Applegate, S., 1965. Tooth Terminology and Variation in Sharks with Special Reference to the Sand Shark, Carcharias taurus Rafinesque. Contributions in Science 86: Los Angeles County Museum, Los Angeles, CA, 18 pp.

Applegate, S. & Espinosa-Arrubarrena, L 1996. The Fossil History of Carcharodon and Its Possible Ancestor, Cretolamna: A Study in Tooth Identification. In The Biology of the White Shark, Carcharodon carcharias. A. P. Klimley & D. G. Ainley eds. Academic Press, San Diego CA, USA. pp. 19-36.

Compagno, L.J., 2001. Sharks of the World, an annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date - Bullhead, mackerel & carpet sharks. FAO Species Catalogue for Fishery Purposes, No 1, Vol 2. FAO Rome. 269pp

Cunningham, S., 2000. A comparison of isolated teeth of early Eocene Striatolamia macrota (Chondrichthyes, Lamniformes), with those of a Recent sand shark, Carcharias taurus. Tertiary Research 20(1-4): pp 17-31.

Shimada, K., 2002. Dental Homologies in Lamniform Sharks (Chondrichthyes: Elasmobranchii). Journal of Morphology Vol 251, pp 38-72

Siverson, M., 1999. A new large lamniform shark from the uppermost Gearle Siltstone (Cenomanian, Late Cretaceous) of Western Australia. Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences, Vol 90, pp 49-66.